NOW DIG THIS!

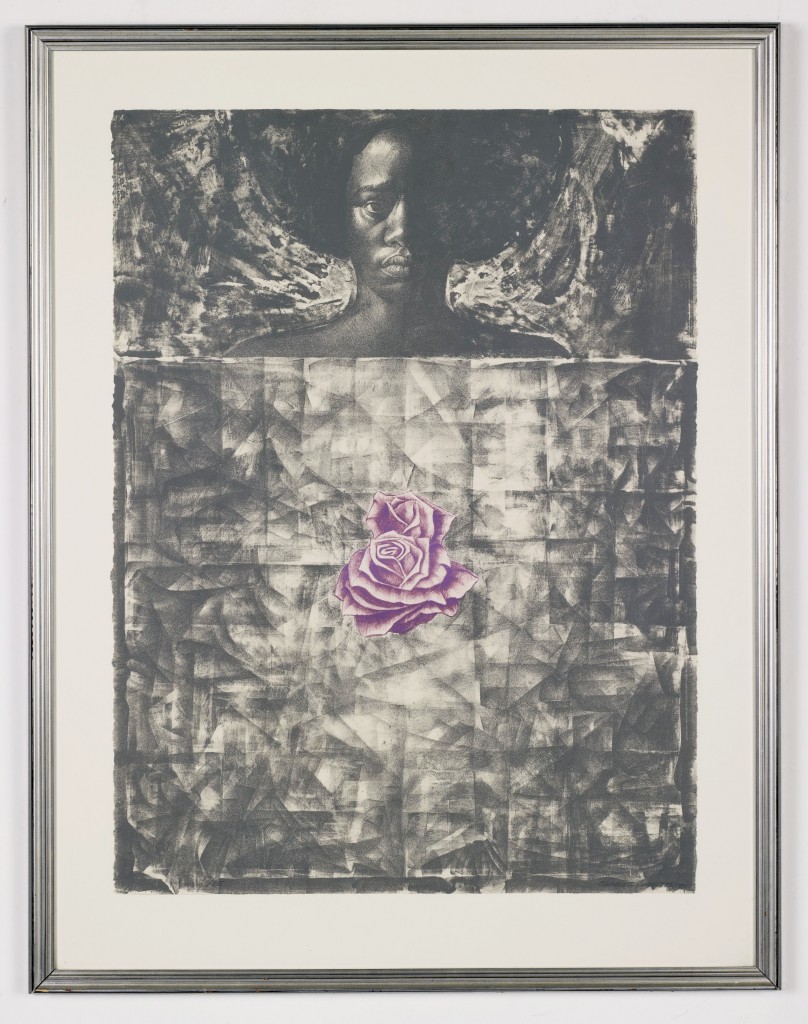

The Now Dig This! Exhibit at UCLA’s Hammer Museum harkens back to an era of social and cultural explosion in Black Los Angeles. From 1960 to 1980 the Los Angeles art scene mirrored the dynamic changes taking place in the U.S. and in the world. Galleries opened, collectives formed, and the definition and language of “Black Art” was exponentially expanded by artists who felt the need to say more. The exhibit speaks of moments in time when African-Americans ventured outside of their oppressed box and made bold statements about who they were and where they were going in the arts and in style. Featuring one hundred and forty works of art from such renowned artists as Noah Purifoy, David Hammons, Charles White, and John Outerbridge, respectively, as well as archival video of The Watts Summer Festival from 1972, the exhibit is a reflection of the tumult and mercurial changes of the pre and post-Watts Uprising era.

This period in Los Angeles, which included the end of the Civil Rights and the entire Black Power movement eras, saw African-Americans go from feeling like the eternal victims to becoming the aggressors in all walks of life, including the art world.

While African-Americans were embracing afros, black fist pick combs, and dashikis, Black artists were eschewing traditional subject matter and mediums and embracing more avant-garde and conceptual styles of creation. In his pieces “Bag Lady in Flight,” “America the Beautiful,” and “Three Spades,” David Hammons used American iconography to convey the idea that African-Americans were finally claiming their spot in this country’s present and future. In “Bag Lady” Hammons uses a series of brown paper shopping bags, some stained with grease and hair, to symbolize the many journeys Blacks have made in this country always in search of freedom and equality. In “America the Beautiful” he uses a print of his own body wrapped in an American flag to say that African-Americans were no longer wiling to be shut out from society and were as American as anyone else.

In artist Noah Purifoy’s untitled assemblage piece he uses collected debris from the Watts Uprising as a remembrance of the intensity and chaos of the event. The bits of clothing and charred debris give one pause to consider each component’s story. In John T. Riddle’s “American Problem Solver” and Dale Brockman Davis’ “Viet Nam Game” the artists use sculpture to air their adversity to the controversial war in Southeast Asia that was going on at that time. Riddle’s piece of a man leaning back almost horizontally in attempts to dodge a bullet speaks to that generation’s reluctance to participate in a war that many saw as unjust.

In Davis’s piece he constructed clay models of the actual bombs being shot and dropped on the villages in Viet Nam and Cambodia. The floor piece gives weight to how much destruction was done in the name of democracy in that part of the world. Another great part of the exhibit is the archival video installation, the highlight of which is a pristine video documenting the 1972 Watts Summer Festival. Putting on the noise-cancelling headphones and watching the event unfold on tape is like traveling back in a funky time-machine. The interviews with the people involved in producing the festival are gritty and unpolished and the awesome performance by the seminal multi-ethnic group War transfers the energy and urgency of that time. You feel, through the subjects’ words and soulfulness along with the stirring music, that all involved rightly believed they were a vital part of the movement.

For any fan of American art history, I recommend making the trip down to the Hammer in Westwood to check out the exhibit to experience and remember this crucial and unparalleled time in Black Los Angeles’s story. Each piece has a lot to say about the artist and the time in which it was created. The exhibit runs until January 8, 2012.